In 2022, I joined the INTO LIGHT Project which seeks to destigmatize addiction by using portraiture and storytelling to create meaningful dialogue about Substance Use Disorder.

On this page, you will find several portraits I created for the California Exhibition alongside narratives created by INTO LIGHT’s writing team. Follow the link below if you’d like to learn more about the Project and view our other exhibitions.

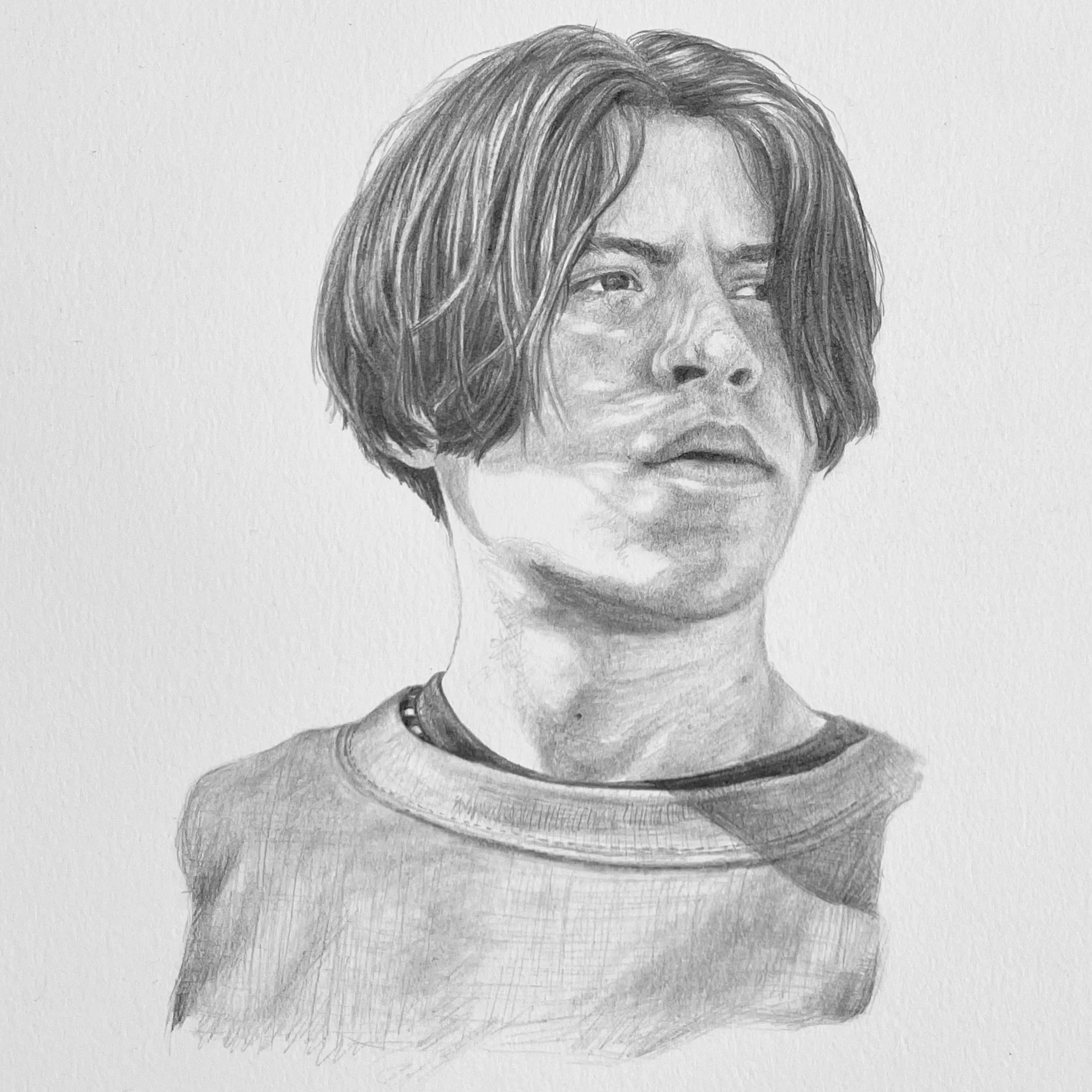

Dylan Kai Sarantos

Authentic, charming, kind, beautiful, talented

Growing up, Dylan lived with his mom Cindy and his older brother Christian, who Dylan became close with in his teenage years. In 2017, his family took a month-long trip to South Africa together, a cherished memory for his mother as she and Dylan grew even closer on that trip. Dylan and his father also got the pleasure of bungee jumping off the highest bridge you can jump from while there.

What Dylan loved most in the world was producing his own beats and writing lyrics for them. He primarily liked goth and emo rap and

he created nearly 30 songs. He was also into photography and was working on a music video before he passed. As a child, Dylan loved dressing up in costumes and trying on crazy outfits. His mother said he always had an eye for fashion. At 17, he mixed his love of aesthetics and his creative mind and began designing and making clothes. Dylan even trademarked his own brand, No Care Cult, which was his statement to the world, telling people to be comfortable with who they are. He designed goth-inspired hoodies, pants, sweatshirts, and more. He was also into tattoos, including a recent one of a spider in a web. On the spider was a pill to remind him not to get stuck in the web of addiction.

Dylan was diagnosed with bipolar disorder when he was 17, which was a big adjustment for him. Before his passing, he was doing dialectical behavior therapy with his mom and working on communication skills and conflict resolution. He was your typical teenager, but he was also responsible and hard-working and had a part-time job to save up for his first car.

Since Dylan passed during the pandemic his family didn’t have a proper memorial, but his friends dedicated a bench to him in one of their favorite hangout spots and decorated it with portraits of him. Many people loved Dylan and have shared stories with his mom about how he changed their lives by being who he was.

Cindy said that the hardest part about living with someone who struggles with addiction was seeing how it changes them. She said it was also difficult to cope, knowing that he didn’t know how to communicate with her about his struggles. Losing Dylan has made her realize how important it is to destigmatize addiction and help people to understand that it is a disease, not a choice. She wants the world to know that counterfeit drugs laced with fentanyl are a real danger that can destroy lives. Since his passing, she has changed her career path and begun working in the mental health field to help other people facing challenges like Dylan’s.

Dylan’s mother, Cindy Cruz-Sarantos, provided the information for this narrative.

April 8, 2002–May 8, 2020

Age 18-Lived with the disease of addiction for three years.

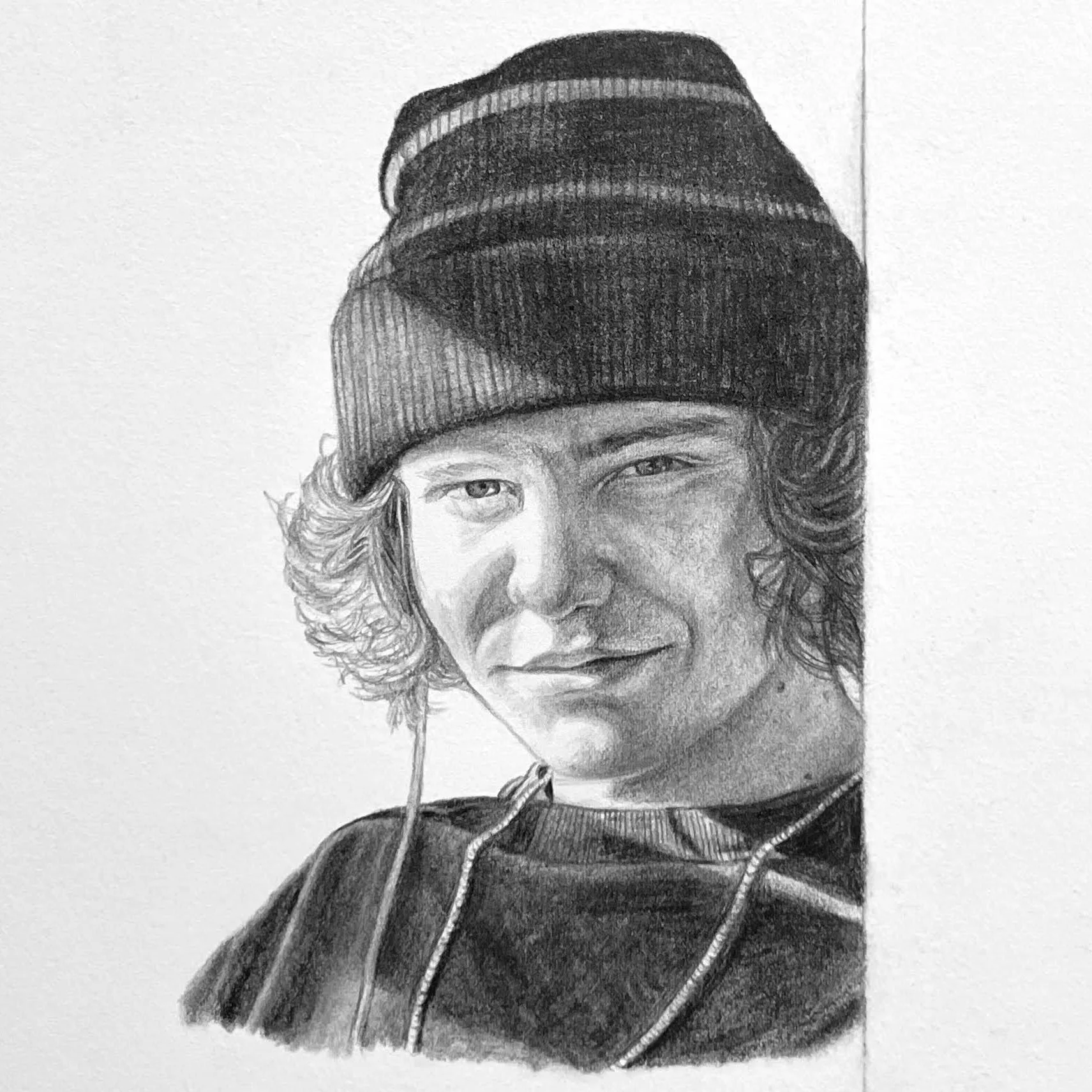

lived with their mom, but then moved in with their dad, where they were closer to the track and motocross friends. They got as much track time in as possible because they both wanted to be professional racers.

The motocross racing caused a lot of injuries to both boys. Harley damaged his knee, which resulted in several surgeries. He was given Vicodin, Percocet, and OxyContin for the pain. “I believe his addiction started then,” his mother said. “It got more pronounced when Harley was in high school and started getting in trouble because of it.” By 13, Harley was riding much less because of his injuries and surgeries but still went to the track to watch his brother and friends.

Harley was artistically talented, creative, and an entrepreneur. He started tagging in ninth grade, which earned him his tag name “Motoe.” He was also into music and discovering the newest, up-and-coming artists. Harley would reach out to them and see them perform live – often at a local music venue called The Observatory. He thought about becoming a mixer and music producer. Another interest was fashion. He found designers before they were well known and started wearing their clothes. When they became popular, he sold what he bought for several times what he paid for it.

After his school troubles, he moved back with his mom for a couple of years but quit school as the addiction got worse. He moved in with his girlfriend and others and started using heroin. “It took him down fast,” his mom said. When Harley got his driver’s license at 16, he signed up to be an organ donor. His mother didn’t know this until the organ donor representatives approached her at the hospital. She wasn’t surprised though, knowing Harley’s giving nature. Several of Harley’s organs were donated to others. The recipient of his liver wrote a book about positivity and dedicated it to Harley. It was very touching.

Harley’s friends still come by and remember him on his Angelversary, the date he passed away. Several have tattoos in Harley’s honor. Laura has joined several support groups where she can talk freely about Harley. She has a “Harley room” filled with his pictures and memorabilia. It doubles as a craft room where she spends a lot of time. She worries about Harley’s brother Cash, now 25, who has had a difficult time with his brother’s death. “It is hard to watch him suffering,” she said. “I lost my son, my sunshine. My son lost his brother, his partner in life. We have both lost part of our future. Once I am gone, Cash doesn’t have a brother to rely on and share his life.”

Harley’s mother, Laura Swank, provided the information for this narrative.

January 8, 1999-February 26, 2018

Age 19-Lived with the disease of addiction for six years.

Harley Lynn “Motoe” Swank

Huge heart, most generous, loyal friend, talented, missed beyond measure

Harley was funny, loved to make people laugh, and was very generous. Two years apart, he and his brother, Cash, did everything together. They were “brothers in arms” and had the same interests. Harley played soccer and was a very talented artist and tagger, but what he was passionate about was motocross. Introduced to it by his father, Chris, he started riding at seven. He and Cash, and the family, practically lived at the track. After his parents’ divorce, the boys initially

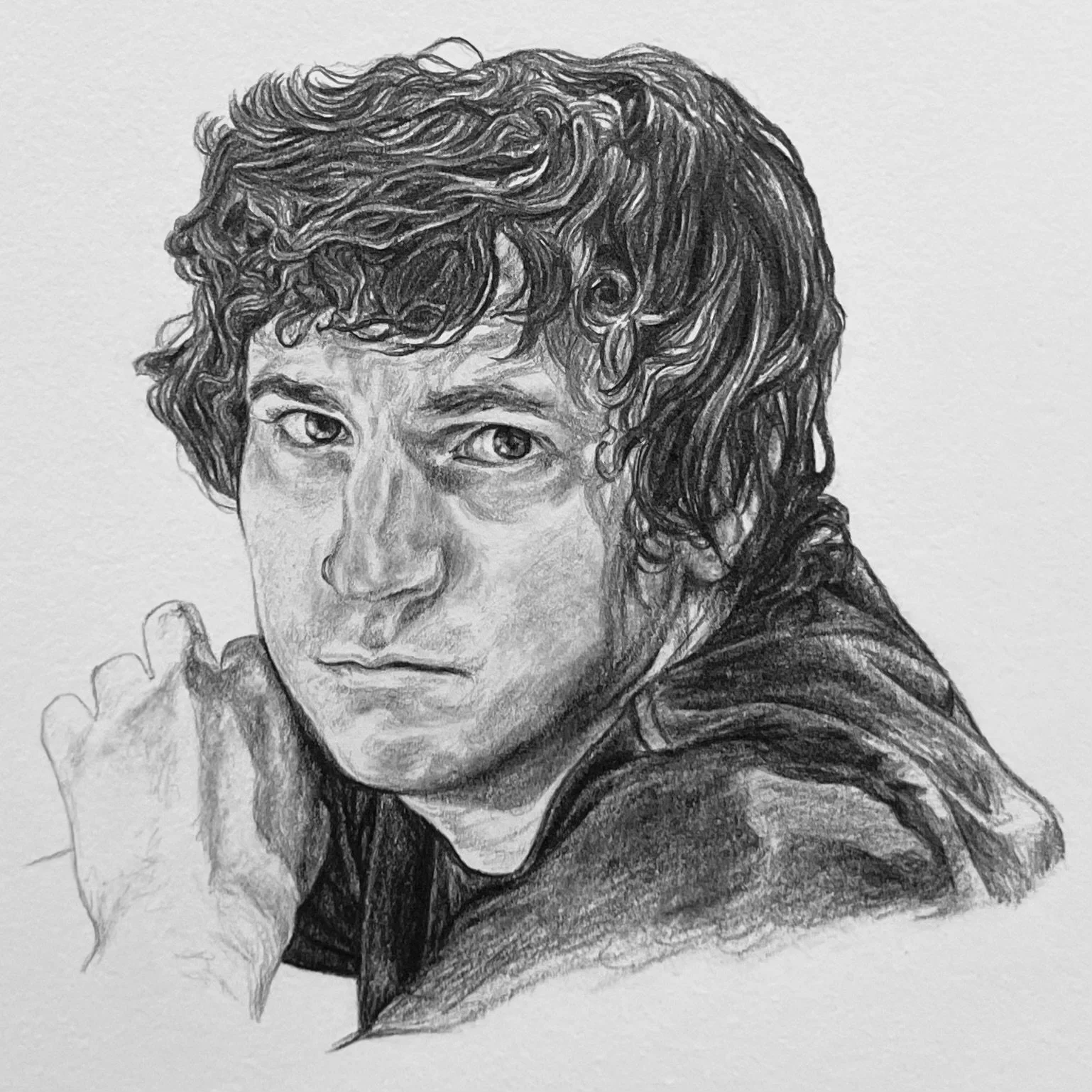

Daniel Puerta-Johnson

A life like no other, fully lived, though short

An only child and first grandchild, Daniel was a rock star in the family. He was everyone’s little kid, light and warm with a loving energy. Until fifth grade, Daniel was the ideal student, a “brainiac” as his dad Jaime put it. He also won attendance and principal’s awards. In sixth grade, something changed. His interests went beyond what school was teaching. He wanted to go deeply to the core and meaning of things, to dissect, not learn by rote.

Daniel had a level of sensitivity and tender-heartedness that attracted many girls to be his friends. A natural listener and counselor, they would go to him for advice about their boyfriends because he was trustworthy and wise. One young woman said Daniel saved her life when she was at a low point.

Daniel adored his dad, was proud of him, and wanted to impress him. His dad admits he spoiled Daniel, providing play stations, skateboards, bikes, scooters, and lots of video games, though he did put his foot down about Grand Theft Auto. “I just wanted him to be the best version of himself,” Jaime said. His mom, Denise, said, “From day one he changed my life. Daniel gave me purpose. He was my bud; he could be goofy with me. There is no replacing that relationship with him. I feel I am still expanding as a person because of Daniel. He is just as much alive with us today.”

Daniel loved nature and all living beings, especially his dog Birdie. He was complex, spiritual, happy, and loving with his friends and family. A humble kid, he enjoyed expensive clothes and nice belongings, but also appreciated what he was given and knew how fortunate he was. Like his dad, he was an entrepreneur. He made money buying and selling t-shirts on Instagram. On trips to his dad’s native country, Columbia, he was a king. His good looks and swagger attracted the attention of many. But the opinion of others did not sway him. He was true to himself.

During a particularly difficult time of Daniel’s active addiction, his parents sent him to wilderness therapy in Utah. He thrived in the desert. When he came back in November of 2018, he was more mature and stable. The sometimes-troubled relationship between Daniel and his dad healed and flourished. Through 2019, Daniel was drug-free, self-reliant, and independent. He and his stepmother, Claudia, were content and playful together, though she had to bug him about having all the plates and glasses in his room!

Since Daniel’s death, Jaime has started a non-profit with other parents called VOID (Victims of Illicit Drugs). VOID educates the public about the problem of fentanyl and counterfeit pills and the prevalence of fentanyl poisoning. “People are being deceived to death,” Jaime stated. Dealers are pressing their own pills with fentanyl and marketing them as prescription Xanax, Percocet, and other medications. They are readily available on social media platforms, and one pill can be lethal. “This is a complex problem, and it will take a lot of motivated individuals to fix it,” Jaime stated. “At first, I wanted to find the person who sold Daniel that drug. Now I am more interested in helping others and saving lives. That’s how I honor my son.”

Daniel’s parents, Jaime Puerta and Denise Johnson provided the information for this narrative.

April 25, 2003-April 6, 2020

Age 16-Lived with the disease of addiction for two years.

Rhonda Saldana (Mama Rhonda)

Loyal, caring, compassionate, funny, quick-witted

Rhonda was a unique, witty, and outspoken woman. She told stories with dramatic emphasis, was funny, and was loyal to the people she loved. Rhonda was passionate about caring for others, especially animals. Frequently, Rhonda would put the needs of others in front of her own. When she was younger, she moved in with her mother and cared for her until her mother passed away. Later, Rhonda moved in with her grandmother to care for her while she was in hospice.

Unfortunately, not long before Rhonda’s passing, she was hit by a car and broke her legs. Her legs never healed correctly and caused severe pain and discomfort when walking. Rhonda had been living with her disabled cousin, taking care of her daily needs, but truly they both needed and depended on each other. Living in poverty was a monumental challenge for Rhonda, and it meant she could not think about the future. Her goal in life was just to get through another day.

Rhonda always took care of the stray cats in her neighborhood because she hated the idea of them not having a home and being unloved. While Rhonda was living with her mother, she found a pregnant cat and raised all the kittens. She took it upon herself to re-home them — a perfect example of her kind heart. Rhonda had a little chihuahua named Nala that went everywhere with her, even if that meant having to sneak her into places that did not allow animals. One of Rhonda’s sister-in-law Maria’s fondest memories with Rhonda is of the day they went to the Narcotics Anonymous Convention and had to sneak Nala into the condo they were staying in. Nala had gotten loose, and Rhonda and her niece and nephew had to chase Nala across the golf course to get her back. They laughed hysterically while 12-year-old Nala outran them.

Rhonda was raised with her sister Rena, with whom she was very close. They grew up in a small, middle-class, family community surrounded by cousins. Rhonda’s addiction spiraled her into poverty, which she experienced throughout the rest of her life. When Rhonda was younger, she had three children: Angela, Anita, and Robert. She was a stay-at-home mom, wife, and an excellent cook. People still talk fondly about the food that Rhonda prepared for them. While Rhonda was in and out of prison, other family members cared for her children. In 2006, Rhonda was released from prison for the final time. She was able to rebuild a relationship with all of her children, but Robert visited her most often.

On Sundays, Rhonda’s sister, Rena, and Maria would visit Rhonda and sit for hours sharing stories while she smoked cigarettes and enjoyed her favorite candy bar, Snickers. They relished these Sunday afternoons and the laughter that came with them. Maria and Rena were Rhonda’s best friends and spent all their holidays and birthdays together. Rena would make Rhonda her favorite chocolate cake for every birthday.

As a worker in the mental health field, Maria says that her goal in life is to help women that are still struggling with addiction, poverty, and abuse. She loves Rhonda and shares her story so that families affected by addiction may not feel so alone.

Rhonda’s sister-in-law, Maria Cantu, provided the Information for this narrative.

January 31, 1964–February 25, 2019

Age 55-Lived with the disease of addiction for 36 years.

Jacob Alexander Lee

Sensitive, hilarious, bright, explorer, troubled

In terms of language, Jake was a late bloomer, not speaking until he was about 18 months old. “Then he spoke in full sentences,” his mother Kristy recalls. “It was in keeping with his personality that he didn’t do things until he was ready to do them perfectly!” He was smart, musically talented, an avid reader, and had a sophisticated and dry sense of humor. Jake had a massive vinyl collection, with hundreds of albums of every genre, all stored carefully in alphabetical order. He always had a book nearby. David Foster Wallace was among his favorite authors.

Jake had a normal elementary school experience and celebrated his Bar Mitzvah at 12. The family took memorable trips to Oregon, Hawaii, and Costa Rica. At 13, Jake disclosed feelings of depression and asked for help. He was put immediately into therapy. “Things got really difficult during middle school,” his mom remembers. “Jake was severely anxious and started self-medicating.” There were multiple calls during his teen years from schools and police about his behavior while drunk or high. After conferring with an educational consultant, Jake willingly went into a wilderness program in Idaho. He knew he needed help. The program was a positive step, and Jake went from there to a therapeutic boarding school in Montana, where he stayed until he was 18. He came home to the full support of his family, a psychiatrist, and therapist, and, later, a drug counselor. He earned his high school diploma. When Jake was 20, he joined his sister and mom on a trip to Thailand where they enjoyed an amazing tour of the country.

Jake wrecked two cars while he was intoxicated and, miraculously, didn’t hurt himself or anyone else. He started working at a local restaurant where he was well-liked and comfortable with many regular customers, some of whom he’d known since childhood. Jake’s self-medication expanded to include Xanax, which gave him some relief from his anxiety. He began Arizona State University’s online undergraduate program, majoring in English, and was steadily progressing toward graduation. He moved to his own, very tidy apartment, which he and his sister Shayna decorated with posters and album art. They were very close. Kristy treasures a phone screensaver image of them on move-in day, sitting on the back bumper of a U-Haul, laughing, and enjoying each other. Jake was figuring out how to live in society. He had taken some acting and improv classes and developed an interest in stand-up comedy. He had plans for his future. Unfortunately, they were not to be. Alone in his apartment, Jake took what he thought was a Percocet. The pill was, in fact, 100 percent fentanyl; Jake passed away.

“Jake was such a great kid; he just didn’t believe it,” his mom says. “He thought he wasn’t lovable.” Kristy misses his sensitivity, his sense of humor, discussing books, and seeing the man he was becoming. “He had every resource available to him, still it was up to him. I know he knew I was always there for him,” Kristy said.

Her advice to others is to enjoy every moment with your kids. Do everything you can to stay connected. Just love them. Kristy is now involved in the Yolo County Opioid Coalition to promote fentanyl education and outreach.

Jake’s mother, Kristy Lee, provided the information for this narrative.

January 6, 1998-April 11, 2021

Age 23-Lived with the disease of addiction for 11 years.

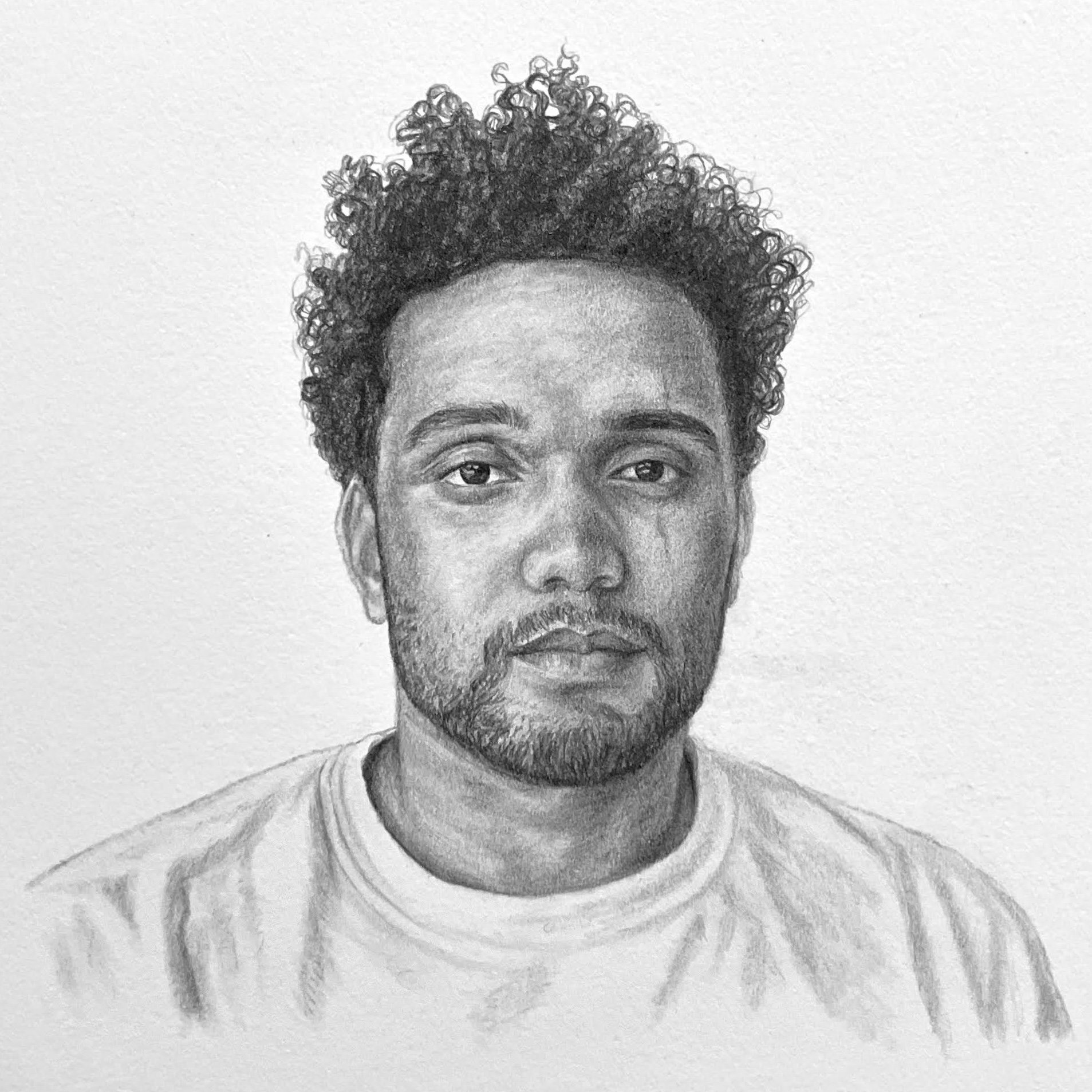

Sage Walker Lewis

Heart-centered, generous, seeker, loyal, suffering

As a kid, Sage was outgoing, joyful, charismatic, and very verbal. People were drawn to him. He expressed interest in people and always helped them to be their best. “He was a pure soul,” his mom, Robin, said. “And gorgeous.”

Sage was a self-taught photographer, videographer, and video editor. He made music videos for his friends and was into the hip-hop scene. After high school, he fulfilled his dream to design streetwear and started a line called Blame LA with his friends. Sage was a natural athlete, a star. He was considered for a college baseball scholarship but preferred to follow his interests directly, rather than go to college and learn from books.

Sage was an only child and close to his parents. The family had fun vacations together, visiting extended family and going to Washington D.C., Alaska, Hawaii, and Jamaica. In school, he was part of the Sports Education Leadership Foundation, which provided opportunities for Sage to travel to Bangladesh to help young athletes develop their skills and to Zimbabwe to build a basketball court and teach basketball and soccer skills. He came home with an empty suitcase, as he gifted what he owned to those he met.

Sage was private about his adoption, at four days old, yet it was a defining aspect of how he viewed the world, as was his mixed race. Having a white mother and black father, both biologically and in his adoptive parents, he felt conflicted about having whiteness in his identity and didn’t want to stand out. Having mixed-race friends helped him manage his feelings. His friendships were profound and important to him; loyalty to each other was a big theme in his relationships. Sage routinely invited people to stay with him and his family. One “temporary” guest ended up staying for three years and was a supportive friend to Sage.

“Sage did well until the pain and shame of addiction took over,” his mom stated. “He lost faith in himself and his ability to succeed.” It was surgery for appendicitis and resulting complications that started the addiction. He was given morphine for the pain and later began self-medicating for anxiety. He lost his confidence and zeal for his dreams. Sage was a natural helper and longed to be of service to people. He was exploring becoming a therapist, but in active addiction, he couldn’t focus enough to enroll.

Sage’s mother, a social worker, said the hardest thing for her was watching him decompensate – losing his ability to maintain psychological defenses – and then return, again and again. She explained, “I felt I was on the line of a great battle in our society that’s defined by mental illness, race, addiction, and politics. Our health system is woefully inadequate. Sage died while the system was failing him.” Robin added, “I have nothing but compassion for all affected by this disease, I have no judgment at all.” Since Sage died, she said, ”he has become my teacher. I know he is okay. He has given me much faith and comfort.”

Robin and Sage’s dad, Stryder, held Sage’s 25th birthday at the ball field that overlooks the city where he played little league. They loaded the bases, sang happy birthday, and released balloons. His mom said, “I love to go up there and think about him where we had so many happy times. I like to see other families enjoying the space and making memories.”

Sage’s mother, Robin Roberts, provided the information for this narrative.

June 25, 1995-January 12, 2020

Age 24–Lived with the disease of addiction for six years.